Brain Organoids and the Law

Brain Organoid Flowchart

I don’t usually write about life sciences topics. I have immersed myself in computers, networks, the Internet, and then artificial intelligence (the computerized variety) since early in my career. Nonetheless, when a news story about “brain organoids” showed up in my Apple News feed,[1] I felt compelled to put on a program about it at the 2022 American Bar Association Artificial Intelligence and Robotics National Institute. The brain organoid panel was entitled, “It’s All in Your Mind: The Legal and Ethical Issues of Lab-Grown Brains.”

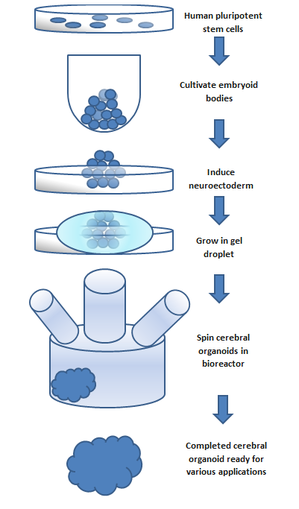

A brain organoid is “a group of cells that dynamically self-organize into structures containing different cell types that resemble some aspects of the fetal brain.”[2] “[H]uman brain organoids are stem cell-derived 3D tissues that self-assemble into organized structures that resemble the developing human brain.”[3] While the panel at the National Institute had “lab-grown brains” in the title, brain organoids are not by any means fully grown human brains and are not even “mini-brains.”[4] They are actually quite small – measured in millimeters. Researchers are growing brain organoids in labs around the country for basic research about brain development, drug and treatment discovery, and studying individual patients. Brain organoids can model dysfunctions related to neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatry disorders, and new research may provide insights into modeling of brain structures and functions.[5]

Why are brain organoids so interesting to those usually comparing human intelligence to silicon-based intelligence? When people think of artificial intelligence, they are mostly examining some form of information technology, but neuroscience researchers are now creating what might be or become a biological-based form of AI. Yet researchers are seeing that such brain organoids are starting to evidence activities that might involve sensing and responding to surroundings similar to what we would expect from a human brain.

During the 2022 American Bar Association Artificial Intelligence and Robotics National Institute panel on brain organoids, we examined the science behind brain organoids, what they are, how they are used in scientific research, and how they compare in capabilities with adult wakeful human brains. The activity shown by organoids in the lab raise ethical and legal concerns because the activities shown by brain organoids are on par with what might be observed from human fetuses.

Scientists are asking tough questions about the possible future of organoids. Could they become sentient and experience some primitive form of consciousness, even though they have no physical bodies and no sensory inputs? They raise broader questions of what are sentience and consciousness, and how would we know if organoids had them. Could sentience and consciousness trigger the need to afford them ethical concern and perhaps even some legal rights?

While the panel at the National Institute broadly explored how the law may view brain organoids and the ethical issues involved in their growth and disposal, this article focuses on the legal issues involved with brain organoids. As an experiment, I undertook legal research using a computerized research service to find where brain organoids appear in court decisions, laws, and legal documents. Unfortunately, no reported cases and no major pieces of legislation or regulation appeared in my search results, probably as a result of the newness of the technology. Nonetheless, some legal documents mention brain organoids, and the legal authorities they relate to shed light on how we can expect the law of brain organoids to develop.

Section I covers the one case in which brain organoids played a role – Trustees of Indiana Univ. v. Prosecutor of Marion County Indiana.[6] Section II discusses a key but unsuccessful anti-chimera bill. If a later such bill became law, it could constrain scientific research on brain organoids. I provide some concluding thoughts in Section III.

I. Trustees of Indiana University v. Prosecutor of Marion County Indiana

The Trustees of Indiana University case involved a state university’s constitutional challenge to Indiana House Enrolled Act 1337 that became effective on July 1, 2016, codified at Indiana Code Section 35-46-5-1.5. The law relates to abortion and the use of fetal tissue from aborted fetuses. That section states:

(a) As used in this section, "aborted" means the termination of human pregnancy with an intention other than to produce a live birth or to remove a dead fetus. The term includes abortions by surgical procedures and by abortion inducing drugs.

(b) As used in this section, "fetal tissue" includes tissue, organs, or any other part of an aborted fetus.

(c) This section does not apply to the proper medical disposal of fetal tissue.

(d) A person who intentionally acquires, receives, sells, or transfers fetal tissue commits unlawful transfer of fetal tissue, a Level 5 felony.

(e) A person may not alter the timing, method, or procedure used to terminate a pregnancy for the purpose of obtaining or collecting fetal tissue. A person who violates this subsection commits the unlawful collection of fetal tissue, a Level 5 felony.[7]

Researchers at Indiana University (IU), its medical school, and other research institutions within IU conduct research into Alzheimer’s disease and other brain disorders. They had been using fetal tissue for experimentation because it has all of the components of the fetal brain, and the fetal tissue acts as a “control” to contrast with a diseased brain.[8] In order to obtain the fetal tissue, IU had “received” shipments of fetal tissue from a research laboratory and therefore arguably violated Section 35-46-5-1.5.

IU alleged that Section 35-46-5-1.5 violated the U.S. Constitution – the Dormant Commerce Clause, the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause, its Due Process Clause (because of vagueness), the Fifth Amendment (because of the alleged taking by the state), and the First Amendment (due to abridging IU’s academic freedom). IU and the Marion County prosecutors cross-moved for summary judgment.

The district court, among other things, granted IU’s motion based on vagueness concerns and enjoined enforcement of Section 35-46-5-1.5. The district court turned aside other IU challenges. The Seventh Circuit, however, reversed the district court’s opinion. The appeals court held that the statute was not unconstitutionally vague, especially given that IU could have sued in state court for a declaration that certain activity was legal. A declaratory judgment action could have clarified the scope of the statute.[9] The Seventh Circuit also rejected IU’s cross-appeal, saying that the First Amendment does not impact the statute’s prohibition of conduct rather than speech,[10] the Dormant Commerce Clause does not apply because the law (as a total ban) also bars intrastate sales,[11] and the Takings Clause does not apply because the researchers did not themselves own the tissue; IU owned the tissue and IU, as a state university cannot sue another part of the state.[12]

In any case, the topic of brain organoids arose in the preliminary injunction proceedings at the district court level. One of the issues at the preliminary injunction stage was whether brain organoids could be a substitute for fetal tissue. The prosecutor defendants submitted a report from David Prentice Ph.D, an academic who served as Vice President and Research Director for the Charlotte Lozier Institute.[13] Prentice contended that fetal tissue was not unique and that organoids could replicate all of the functional and developmental aspects of normal organs.[14] Since organoids are developed from induced pluripotent stem cells from adults or adult stem cells, using fetal tissue is not necessary, for instance to investigate Zika virus infections.[15]

IU, however, submitted two declarations of academics, Larry Goldstein, Ph.D.[16] and Irving Weissman, M.D.,[17] to rebut the claim that brain organoids are adequate substitute for fetal tissue used by IU researchers. Goldstein claimed that, although organoids are valuable, they are not a substitute for fetal tissue because organoids are missing key cell types, and fetal tissue will be necessary for the foreseeable future.[18]

Weissman asserted that organoids generally are not substitute for fetal tissues, again because they lack cell types needed to replicate organ functions. “[B]rain organoids lack crucial cell types and brain regions to guarantee a prospectively isolate brain stem or progenitor cell could repopulate within the organoid and give appropriate functions.”[19] Accordingly, “organoids are not equivalent to or interchangeable with human fetal tissue.”[20]

My intent to discuss these expert documents is not to resolve the scientific question of whether brain organoids are or are not adequate for research purposes without using fetal tissue. Instead, I conclude that until brain organoid research becomes more common, use is more widespread, and more disputes about organoids themselves arise, courts’ exposure to brain organoids is likely to come from expert documents and testimony. We will have to await lawsuits in which brain organoids are at the heart of the dispute.

II. Anti- Chimera Legislative Efforts

Some researchers are implanting human brain organoids into mouse brains.[21] “In this way, there [is] a ‘fusion’ between the [mouse’s] host tissues and the human brain organoid, which was able to develop functional neuronal networks and blood vessels in the grafts.” Mixing human tissues with an animal host, however, results in the creation of an animal that is part human and part animal – a “chimera.”

One question that may arise to these researchers is whether the law prohibits the creation of chimeras. At the federal level, legislators have introduced anti-chimera legislation, but no such bill has passed. Given the interests of some legislators in restricting scientific research to alter natural humans, we can reasonably anticipate future legislative proposals in this area. If we have a change of administration in the future, there may be enough support to pass and sign anti-chimera legislation. Using the latest unsuccessful anti-chimera bill as a model, it would be wise for researchers and their research institutions to consider how anti-chimera legislation may affect their ability to implant brain organoids in mice.

The last anti-chimera legislative proposal was the Human-Animal Chimera Prohibition Act of 2021 (the “Act”).[22] The Act would have added two sections to Title 18 of the U.S. Code. The first section, Section 1131, would have established definitions. The operative section, section 1132, would have prohibited chimeras. More precisely, the Act would have prohibited knowingly creating or attempting to create a “prohibited human-animal chimera” in otherwise affecting interstate commerce. The penalty for violating section 1132 would be fines or imprisonment of up to 10 years, as well as civil fines that are the greater of $1 million or twice the amount of pecuniary gain from a defendant’s activities.[23]

“Prohibited human-animal chimeras” are defined in part as embryos of various kinds with mixed human and animal DNA.[24] Nonetheless, implanting brain organoids in mice does not involve mixing human and animal DNA within a single embryo. The Act’s definition of “prohibited human-animal chimera” also includes making a nonhuman life form that allows human gametes to develop within it or exhibits human facial features or body morphologies.[25] Again, implanting human brain organoids does not involve either of these two procedures. So far, it appears that the Act would not have affected implanting brain organoids into mice.

The definition, however, also covers developing “a nonhuman life form engineered such that it contains a human brain or a brain derived wholly or predominantly from human neural tissues.”[26] This part of the definition does potentially affect organoid researchers. The mice in question are nonhuman life forms and would have a brain containing human neural tissues. Nonetheless, mice with today’s small brain organoids would not have brains developed wholly or even predominantly from human tissue. To the contrary, in current scenarios of usage, a small human brain organoid is implanted in a full-size mouse brain. Therefore, the vast majority of the animal’s brain tissue is from the mouse itself. Consequently, it does not appear that a mouse with today’s typical brain organoid would fall within the definition of a prohibited human-animal chimera.

In addition, the Act has a rule of construction stating that the Act does not prohibit research involving transplantation of human organs, tissues, or cells into animals if such activities are not prohibited under the main body of the Act. Brain organoid researchers are certainly transplanting human tissues into animals, namely mice. However, the rule of construction does not provide a safe harbor for all instances of transplanting brain tissue into mice. Placing a whole human brain into an animal or creating an animal whose brain is predominantly human tissue would violate the Act and therefore the rule of construction would not save such conduct. Today’s brain organoid researchers, however, would not need the help of the rule of construction because they don’t otherwise fall within the Act, as explained above. In sum, if future legislation were to track S. 1800, it would not affect researchers placing today’s (tiny) brain organoids into full-size mouse brains.

III. Conclusions

We are in early days when it comes to brain organoids and the law. There are no reported cases or major pieces of legislation or regulation affecting brain organoids. Nonetheless, brain organoids are gradually entering discussions in the legal realm indirectly through expert materials or general laws that could impact what researchers do with brain organoids. We will have to await future developments in the law to see how the law will directly affect brain organoids.

[1] Caroline Delbert, Experts Fear Lab-Grown Brains Will Become Sentient, Which is Upsetting, Popular Mechanics, Oct. 28, 2020, https://www.popularmechanics.com/science/a34499861/lab-grown-brain-organoids-sentient/.

[2] Harpeet Setia & Alysson R. Moutri, Brain organoids as a model system for human neurodevelopment and disease, 95 Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology 93 (2019), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6755075/.

[3] Andrea Lavazza & Federico Gustavo Pizzetti, Human cerebral organoids as a new legal ethical challenge, 7 J. of L. & the Biosciences 1, 3 (2020) (citation omitted), https://academic.oup.com/jlb/article/7/1/lsaa005/5854398.

[4] Francesco Puppo & Alysson R. Moutri, Network and Microcircuitry Development in Human Brain Organoids, Biological Psychiatry, Aug. 5, 2022, at 2, https://www.biologicalpsychiatryjournal.com/article/S0006-3223(22)01437-8/fulltext#articleInformation.

[5] Id. at 1.

[6] 289 F. Supp. 3d 905 (S.D. Ind. 2017), rev’d sub nom. Trustees of Ind. Univ. v. Curry, 918 F.3d 537 (7th Cir. 2019).

[7] Ind. Code § 35-46-5-1.5 (emphasis added).

[8] See 289 F. Supp. 3d 912-13.

[9] See 918 F.3d at 540-42.

[10] See id. at 543.

[11] See id.

[12] See id. at 543-44.

[13] David Prentice, Ph.D., Report Regarding Fetal Tissue Research and Ethics, ECF. No. 77-16.

[14] See id. at 3, 6.

[15] See id. at 6.

[16] Declaration of Larry Goldstein, Ph.D., ECF No. 77-14 [hereinafter Goldstein Decl.].

[17] Declaration of Irving Weissman, M.D., ECF No. 77-15 [hereinafter Weissman Decl.].

[18] See Goldstein Decl., supra, at 9.

[19] Weissman Decl., supra, at 13.

[20] Id.

[21] See Puppo & Moutri, supra, at 3; Lavazza & Pizzetti, supra, at 4.

[22] S. 1800, 117th Cong. (2021).

[23] See id. § 2.

[24] See id. § 1.

[25] See id.

[26] Id.